Struggling Farmers See Bright Spot in Solar

Monday, September 23, 2019

Panels take land out of crop production but generate energy revenue. ‘Solar becomes a good way to diversify.’

Re-posted from a Wall Street Journal article by Kirk Maltais, September 23, 2019

U.S. farmers are embracing an alternative means of turning sunlight into revenue during a sharp downturn in crop prices: solar power.

Solar panels are being installed across the Farm Belt for personal and external use on land where growers are struggling to make ends meet. The tit-for-tat tariffs applied by the U.S. and China to each other’s goods have cut demand for American crops. Futures prices for corn, soybeans and wheat are all trading around their lowest levels since 2010. Making matters worse, record spring rainfall left many farmers no time to plant a decent crop.

The revenue that Dick and Jane Nielsen earn from the corn and soybeans they grow on 3,500 acres outside St. Paul, Minn., has dropped by about 30% over the past six years. The Nielsens are planning to make up some of the shortfall with the roughly $14,000 that a local utility has agreed to pay them annually for the next 22 years to operate an array of solar panels on 15 acres of their land.

Photo: Tim Gruber for The Wall Street Journal

“It’s something to live on until we’re gone,” said Mr. Nielsen, 77 years old.

Farmers have two options for adding solar power on their farms: lease land for energy companies to generate power to funnel electricity into the grid, as the Nielsens are doing; or install their own solar panels to cut their electricity bills. Both methods can amount to more than $1,000 a month in improved margins, according to farmers and renewable-energy advocates.

“There’s absolutely growing interest in farmers improving their income streams,” said Rob Davis, a director with Fresh Energy, a St. Paul nonprofit that has worked with a few hundred farmers in 30 states to add solar power with environmental benefits to their operations.

Some farmers say they are hesitant to sign control over their land to power companies for years at a time. If crop prices rebound, they say, rent from power companies could fall behind what they could make growing crops on that land.

Rising Sun

Farmers are contributing to the rise of solar power capacity in the U.S.

Sources: U.S. Energy Department; National Renewable Energy Laboratory; WSJ calculations (acres)

But the worst downturn in decades is leading others to take that risk. Farm bankruptcies, known as chapter 12 filings, increased 13% in the first half of this year to the highest level since 2012, according to the American Farm Bureau Federation.

“There’s been very little profit at the end of the year,” said Dan Adams, a corn and soybean farmer who this year leased all of the 322 acres he owns in Iowa County, Wis., to a solar-power cooperative at a rate of $700 an acre annually. He plans to continue farming on 420 rented acres nearby.

“Solar becomes a good way to diversify your income,” he said.

The advance of solar installations on farms follows the installation of huge wind turbines across the Farm Belt over the past decade. About 15,000 of the roughly two million U.S. farms contained wind turbines in 2017, the most recent year for which data is available, up from about 9,054 in 2012, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Solar power—in some cases from small installations used to heat buildings or run equipment—is more widespread. Some 90,000 farms used solar equipment as of 2017, according to the USDA, three times the number using solar panels in 2012.

The National Renewable Energy Laboratory, a division of the U.S. Department of Energy, estimates that solar panels will cover three million acres by 2030. That compares with almost 258,000 acres generating solar power in 2018, according to Wall Street Journal calculations based on data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

The way farmers incorporate solar power into their operations depends on how favorable a state is in offering benefits.

States that encourage funneling locally produced solar power to utility companies are seeing more instances of landowners leasing their acres, said Autumn Long, a regional director with Solar United Neighbors, a nonprofit in Washington, D.C. “But in places that do not incentivize large-scale solar development, farmers are constricted to installing solar to help meet their own energy needs.”

The average cost to install solar is $2.99 per watt, according to online solar marketplace EnergySage. The average home system is 6 kilowatts, which costs homeowners nearly $18,000 before tax credits; but for farmers who need much more power, these costs can range from $40,000 to over $100,000.

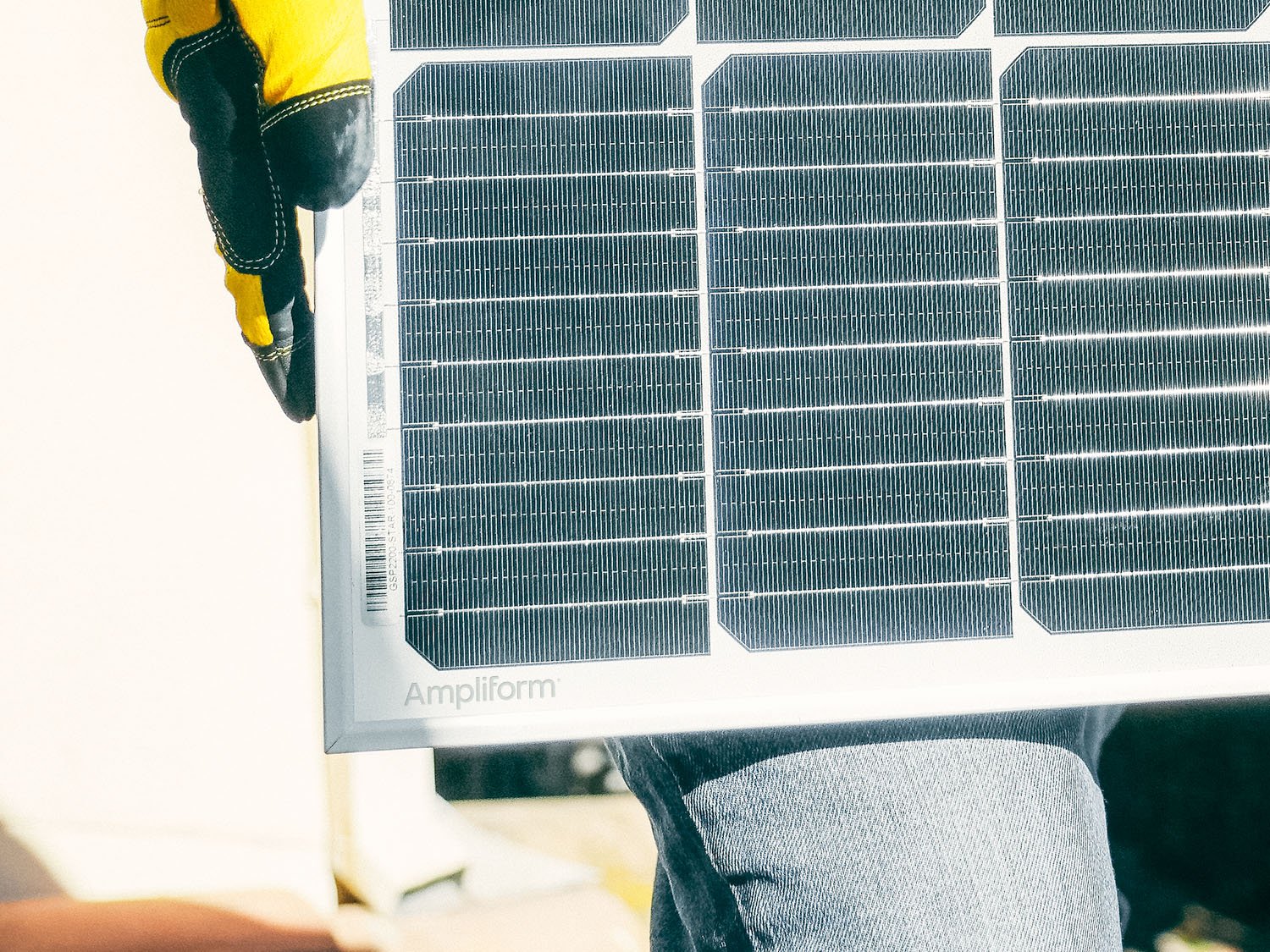

Steve Nightingale, a corn and soybean farmer in Henry County, Ill., who recently installed solar panels on one of his fields, said his monthly electricity bill used to rise to $1,000 during harvest. This spring and summer, power from the panels covered his bill for four straight months.

He has also earned credit for 8.5 megawatt hours of future use that his panels have fed back into the local power grid.

“You’re always looking for a return on investment in tougher times like these,” Mr. Nightingale said.

Photo: Tim Gruber for The Wall Street Journal

Corrections & Amplifications

Steve Nightingale has earned credit for 8.5 megawatt hours of future use that his solar panels have fed back into the local power grid. An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that he earned credit for 8.5 megawatts of future use. (Sept. 23, 2019) Also, 8.5 megawatt-hours of future use is enough to power one home in Illinois for a year. An earlier version of this article incorrectly said it is enough to power roughly 1,190 homes in Illinois for a year. (Sept. 27, 2019)